- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Diaries of Franz Kafka

Diaries of Franz Kafka Metamorphosis and Other Stories

Metamorphosis and Other Stories The Castle: A New Translation Based on the Restored Text

The Castle: A New Translation Based on the Restored Text The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories In the Penal Colony

In the Penal Colony The Trial

The Trial Amerika

Amerika The Burrow: Posthumously Published Short Fiction

The Burrow: Posthumously Published Short Fiction Sons

Sons Letters to Milena

Letters to Milena Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures

Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures Collected Stories

Collected Stories The Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China The Burrow

The Burrow The Castle

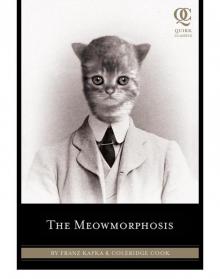

The Castle The Meowmorphosis

The Meowmorphosis The Sons

The Sons The Lost Writings

The Lost Writings The Unhappiness of Being a Single Man

The Unhappiness of Being a Single Man Amerika: The Missing Person: A New Translation, Based on the Restored Text

Amerika: The Missing Person: A New Translation, Based on the Restored Text The Burrow: Posthumously Published Short Fiction (Penguin Modern Classics)

The Burrow: Posthumously Published Short Fiction (Penguin Modern Classics) The Diaries of Franz Kafka

The Diaries of Franz Kafka Investigations of a Dog

Investigations of a Dog The Metamorphosis and Other Stories

The Metamorphosis and Other Stories The Trial: A New Translation Based on the Restored Text

The Trial: A New Translation Based on the Restored Text